BLOG

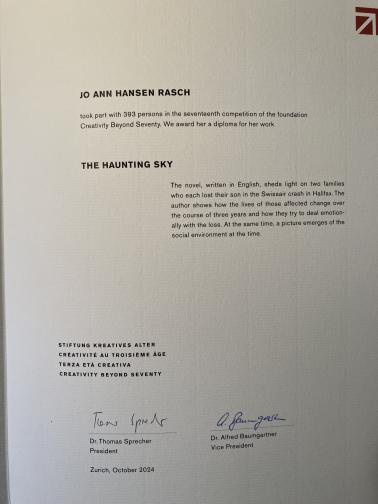

October, 2024 - The Haunting Sky

When searching for a subject about Switzerland, I was astonished to discover that no Swiss author had written about a period of major national transformation. This occurred in the last years of the twentieth century and the beginning of the twenty-first century. Amazed by the lack of creative curiosity, I wrote in English my novel The Haunting Sky.

In September 1998 a Swissair jet crashed into the sea near Halifax, Canada, killing everyone onboard. This was a shock that reverberated across the world. Switzerland had a reputation of perfection. Even we thought we were perfect. Several years before, we had rejected EU membership, so certain were we of our independent pragmatic nature. About the same time as the crash, the World Jewish Congress attacked Swiss banks for mishandling or even stealing Jewish deposits that dated from WW2. We had trouble listening. There were also angry debates about health insurance prices, the invasion of foreigners, and the unknown but fast-changing world of electronics.

In October 2001 Swissair was abruptly grounded. After the economic downturn following the September 11 attacks in the USA, Swissair was unable to control a huge debt due to irresponsible overextension. The grounding occurred so suddenly that pilots had to pay fuel out of their own pockets or with the help of passengers to return jets to Switzerland. The Haunting Sky covers this shocking event.

I believe my book, hopefully translated into German or French, has its place in Switzerland. Two years ago, I sent it off to Creativité au Troisième Age, a foundation based in Zurich, which accepts work in different languages from people aged over seventy. This summer I received a letter saying I had received a distinction. Wow, I thought. This distinction has given me the courage to send my manuscript off to a few editors here in Swiss romande. Who knows? Maybe for my eightieth birthday I will find a publisher for The Haunting Sky.

January, 2022 - Books in covid time

I am writing from our home in Lutry where Marc and I have sheltered due to COVID. Lutry was founded as a littoral neolithic settlement and a line of menhirs still stand facing the lake. The view of the medieval town, Lake Geneva and the French Alps is stunning. In our garden, where once bears and wolves roomed, we have a friendly red robin and other delightful birds that keep us company.

We are fortunate, but people are suffering. We have come to understand viscerally how much we are part of nature, how much we are one world. Some of us belong to several communities, speak diverse languages and carry multiple passports. Many more are refugees without any papers. My COVID diary shows that in a year we have made a leap into the unknown about ourselves and our planet. Books, reading and writing them, are an essential pleasure.

3500 years ago in Lutry

February 2021 - Celebrating Mrs. William Tell

Two envelopes, one for my husband and one for me, arrived with our voting cards. His was addressed to Mr. Marc Rasch. Mine was to Mrs. Marc Rasch. It was just after February 7th 1971 when Swiss men finally gave Swiss women the right to vote. For ages women had demanded their rights in the usual quiet orderly way that the Swiss run their country but they were ignored or scorned by men. I had been married for seven years and though I was finally recognized as a citizen, I wondered what had happened to Jo Ann Hansen?

The day we women got the right to vote we were expected to devote ourselves to other people’s needs in much the same way Mrs. William Tell had done 800 years before. I came from New Zealand where women received the right to vote in 1893, the first country in the world to recognize that women were politically, mentally and legally the equal to men. Both my grandmothers worked outside their homes. Granny Daisy ran a hostel for young farmhands who had returned from war and were intent on finishing their education at Christchurch Technical College. Granny Black, a war widow, owned and directed a company that dealt in supplies for farmers. My university educated mother was an artist. I loved my Swiss husband but his country angered me.

In Switzerland, after women got voting rights, I was determined to reclaim my own life even though I knew more time was needed to change centuries of paternalism. Ten years after women officially became citizens, gender equality and equal pay for equal work was written into the Swiss constitution. But wives still could not work, chose where they would live, open a bank account, take their children on a foreign holiday or manage their personal finances without their husband’s permission. The husband remained the head of the household until a 1985 referendum granted equal rights within the family circle. By this time I had graduated from night school and worked as a teacher while publishing stories. Proudly, I had my name legally changed to Jo Ann Hansen Rasch.

On February 7, 2021, Switzerland celebrated the fiftieth anniversary of women’s voting rights. Mrs. William Tell would be delighted to know how much progress we have made. I believe today she might be the one to claim Switzerland's independence and successfully send an arrow through the apple on her son’s head.

Jo Ann at the manifestation for Christiane Brunner’s election. With ten thousand other women, she demonstrates in front of the Federal Palace in Bern the 10th of March 1993.

Our daughter Eliane with her daughters Roxanne and Victoria at Victoria’s 25th birthday in 2020.

Our son Christophe with his sons Elliott and Nathanael in 2020.

March 2019- Accidents and a New Way of Writing

As I crashed to the ground I split in two. I saw the back of my silk shirt decorated with red roses as I walked away. That person had to get away. I knew I’d never see her again. On the pavement I was the crushed elbow, the gushing fountain of blood from my chin, a woman in pain and shock. I have no memory of the six hours, from midnight to morning one busy Friday evening, when the medics operated. They wanted to save my arm, my left arm, the one that wrote stories. A plate, screws and a prosthesis, all joined together to give me a new arm.

Outside my hospital window a chestnut tree transformed green into bruised yellow. When I closed my eyes an elephant, her eye so close to mine, insisted on her compassionate presence. How I loved you Morpheus, god of dreams. People talk about pain, divide it into categories, give it numbers one to ten. In the flood of darkness, extinguishing all light, pain was simple.

Months after my accident I still couldn’t hold a pen. Complex Regional Pain Syndrome had been diagnosed, a disease that was attacking the peripheral nerves in my hand. It looked like a piece of red meat. More excruciating therapy... I was learning how to cheat my brain into believing I was not a cripple. A year later a second operation removed the plate and a splinter of broken bone that dug into a nerve. The post delivered the plate and thirteen screws in a labeled plastic bag.

Could I ever write again? Friends told me how lucky I was to live in the age of computers when writing flowed easily. But my writing came slowly from somewhere below my ribs, an undigested feeling of fear or anger or love and then it lingered in my bloodstream until it rambled down my left arm to my fingers with words forming along the way. I was not ready to write differently.

Then I fell again, this time tripping over uneven pavement one dark night. First my right knee and then my left hand received my weight. Two broken bones in the hand and a knee replacement followed. Bionic was my new name. I sulked and cried, angry with myself, angry with the world. My husband Marc withstood the waves of misery and waited. He believed I wasn't a person who gave up easily.

Recovery came slowly. But a writer is always a writer, and eventually I turned to my computer. I wrote a short poem, then another. Much later I was able to hold a tiny pencil and put words on paper. FIrst, a letter to Marc thanking him for his patience and most of all his love. Today, the computer has become my friend, I write only rarely with a pen, and don't miss it at all.

July 26, 2011 - Julian of Norwich

I was seeking Julian, the first woman to write a book in English. She had lived in Norwich, England, seven hundred years ago. She is known as Julian of Norwich, her first name taken from the local church Saint Julian’s where she lived, as an anchoress, in a small room adjoining the church. One shuttered window in the common wall facing the sanctuary allowed her to participate in the mass and another window opened up to the outside world. There is no mention of her in any religious order.

I was seeking Julian, the first woman to write a book in English. She had lived in Norwich, England, seven hundred years ago. She is known as Julian of Norwich, her first name taken from the local church Saint Julian’s where she lived, as an anchoress, in a small room adjoining the church. One shuttered window in the common wall facing the sanctuary allowed her to participate in the mass and another window opened up to the outside world. There is no mention of her in any religious order.

An anchoress or anchorite was one of the earliest forms of Christian monastic living, quite widespread during the Middle Ages. Withdrawing from secular society the person led a prayer-orientated ascetic life. Julian was reputed to be wise and she often gave spiritual advice and counsel to her visitors through the outside window.

Norwich is situated in an interesting area for bird photography and my husband, when he heard my plans, decided to accompany me. We divided up the week so we were bird watching on the Norfolk Broads one day and then on the other I followed my quest.

I was seeking a spiritual space of my own, not one imposed on me by generations of men, and I felt Julian could help me. Over my lifetime, as a woman, I had gained much in the legal, social and economic areas, but what I felt about the soul had little connection to what I encountered. What my body knew was not connected to any religious dogma, nor my intuition and consciousness to objective reasoning. My wisdom, gained from a lifetime of seeking, seemed to have little reality in the outside world. Julian offered me a powerful feminine image from her book The Revelations of Divine Love. “God all wisdom is our loving Mother.” The Church could easily have condemned this as blasphemy, but her book is considered a spiritual classic, unparalleled in English religious literature.

After Marc and I arrived in Norwich I set off for a short walk around our hotel. The district was called Tombland because hundreds of plague victims were buried there. I wondered if Julian, before she entered her retreat, could have lost children in the plague? Julian’s long life spanned parts of the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries. At that time the Black Death struck rich and poor alike. In Norwich, bad harvests followed quickly one upon another, and hunger and desperation invaded the town and surrounding countryside.

Those centuries saw England in the age of chivalry. Chaucer wrote The Canterbury Tales and the Hundred Years War dragged on against France. A husband was easily lost in such long term fighting. Norwich, a walled city of consequences, was then famous for its wool and weaving. While visiting the open market, I stopped at a stall where a woman was selling hand-knitted articles.

“What a beautiful jacket,” I said. “You’re an artist.”

The woman smiled. “My family’s been in this business for centuries, right here in this market.”

“Would you know anything about Julian of Norwich then? She lived in a cell next to Saint Julian’s Church in medieval times. I’m trying to find out about her.”

“You know, we’ve been connected to this area for as long as my family remembers and the Middle Ages was tough for everyone. In Northern Europe many women developed passionate individual forms of religion at that time.”

“But she wrote a book, in fact she was the first woman to write one in English.”

“Maybe…but I don’t have time for that stuff. Look at the competition I’ve got.” She pointed in the direction of a couple of stands where brilliant silks and cottons, surveyed by their Indian or Pakistani owners, were laid out in rainbow order to attract buyers.

I left her stall, jostled by the crowds. Why, for the first time in English history, had a woman of no special importance or education written a book in Norwich? Shouldn’t she have been running a market stall or her husband’s house? Twenty or thirty years after finishing her manuscript, Julian composed a longer version of the same book. She had probably learnt to read and write to accomplish these tasks because most women were illiterate then.

Early the next morning, the enchantment of spotting a barn owl undulating across a freshly ploughed field dispelled my peevishness. On the Norfolk marshes searching for waders, I watched a purple sandpiper dance about on a rock, pecking at mossy seaweed, while the bitter North Sea waves splashed the rock’s surface. I knew the bird made a scrap of a nest on bare ground. Its alarm call was loud rapid laughing, “pehehehehehe…” This dumpy creature seemed to defy reason, but it lived fully as nature ordained.

On Sunday, while listening to the cathedral choir’s hymn singing during a traditional Palm Sunday service, I realized I wanted Norwich to be as noble and pure as the voices that lifted me up into spiritual bliss or as nature blossomed in the spring sunshine. If Julian had had such an extraordinary drive to write, then I had hoped to find a place of inspiration; not this town that had the dubious record of being the first European town where a case of blood accusation resulted in a massacre of Jews. While Julian lived the town’s council also condemned people to be burnt at the stake because they questioned the Catholic Church. The smell of their burning flesh and their cries of fear and agony probably drifted into Julian’s cell.

I sat in the cathedral pew, but my mind wandered. I left the horrors of history and thought about the fenlands, flattened below a vast expanse of sky. I daydreamed about the daffodils swaying, inaudible in movement, along the winding riversides, and visited the hedgerows aglow with hawthorn flowers. High up on the cathedral steeple a pair of peregrine falcons were nesting. I had seen one, with closed wings, make a spectacular swoop on a hapless sparrow. For all its violent selection of life and death, nature restored me whenever I got too close to human cruelty.

When the Dean stood up to deliver his sermon my attention returned to the solemn cathedral service. The Dean spoke of our habit to exclude the narrative of the other, even to cultivate conflicting narratives. It was the week of sudden uprisings against tyrants throughout the Arab world and the devastating earthquake, tsunami and atomic alert in Japan. “We still think we can run the world better than God,” the Dean said.

A vision of the barn owl appeared, flying ghost-like towards me, and then I remembered the ancient misogynous fable that women had no souls. I thought many women believed they could run the world better than men. I’m not sure they put God in the equation.

I left the cathedral and wandered over to the newly reconstructed St. Julian’s Church, only a few blocks away. During the Reformation the outside cell had been demolished. During W.W. II the church received a direct hit and was badly damaged. Nothing physical, except for a couple of manuscript copies of her book, was left of Julian’s life.

I sat alone in the rebuilt cell with my feet up on a bench and recalled the stories, both about Julian’s time and mine. They were similar in many ways. I thought about the terrifying dysfunctional force out there in the world seeking to ensnare and entangle. Julian had written, “and all shall be well,” a strange remark considering her knowledge of human beings, but indicative of her obsessive faith. As a woman who had spent most of her life living as a foreigner, I knew there were always several points of view. Rejection was as familiar as misunderstanding.

My body felt soft and fragile against the wooden bench. My mind continued to twist and turn. I did not possess Julian’s visions but I had a mysterious need to write which was part of my spirituality. Creativity was essential to my life. Julian, who understood the purpose of her life, wrote, “God is love.” Julian found her truth in that mystical being called God. She needed to share their relationship to the point that all the rest seemed unimportant. Writing was essential to Julian too and maybe our reasons were not so different. But if Julian meditated, prayed and wrote, she also knew how to listen, not only to God but also to her neighbors. I would remember that about her.

March 20, 2011 - Geneva Writers Group

Susan Tiberghien (far left) with GWG members at the Press Club

Susan Tiberghien (far left) with GWG members at the Press Club

On January 23, 1993, a group of seventeen English-language writers gathered for a workshop on the first floor of the long-established Café du Soleil in Petit-Saconnex. Some of these writers had been with Susan Tiberghien in a writing workshop at the American Women’s Club; others had met with her in an evening workshop open to men and women. Geneva is a city of transitions and traditions, a lonely place for writers who have been up-rooted, and Susan, a born leader, wanted to share her passion for writing.

For the next three years she taught workshops on different aspects of creative writing to this small group of writers who named themselves the Geneva Writers’ Group. In September 1996, a more formal structure was established. By then, Susan, already a mother of six and a grandmother, had become an inspiring writing instructor as well as a published author. She gave a morning workshop, with handouts and writing exercises, and led a critiquing session in the afternoon. Thirty members now belonged to the GWG with seven of them forming a steering committee. Workshops took place once a month, from September to June, and were open to all who wished to develop their writing skills in English. Both beginning and published writers were welcome. Membership was eligible to those who attended three workshops a year.

In 1997 the anthology Offshoots Vol. IV was published, a joint venture by the American Women’s Club and the GWG. The authors, writing in Geneva, were from fifteen different countries. The anthology, a biennial collection of prose and poetry, had originated at the American Women’s Club. In 1999, the GWG published Offshoots V alone. This was the beginning of bookstore readings, radio competitions and reading invitations from different associations including the US Embassy. Master classes, the first on poetry given by Wallis Wilde Menozzi, were also initiated.

Communication was going electronic and by 1998, when the group held its first international writing conference at Webster University, professionals on the business of writing were already offering panels on new and different aspects of editing, publishing, promotion and production. The weekend conference also gave high-level instruction in fiction, play writing, creative non-fiction and poetry.

In September of that same year, in need of bigger premises, the GWG moved to the Geneva Press Club. The elegant old building, La Villa Pastorale, which housed the Press Club, was not far from the Café du Soleil so writers could still return there for lunch.

A new millennium offered an affirmation of life and the GWG seized this moment to consolidate its core goal of sharing a love of writing. On May 15, 2004, by-laws were written and approved by members and the Geneva Writers’ Group was registered as a non-profit association. Other amenities followed: a service that co-ordinated small independent groups, a mentoring service, literary salons, play production, and a biennial Meet the Agents weekend. As of today there are 170 members from 30 countries. There have been seven international writing conferences and in 2009 the twentieth anniversary of Offshoots was celebrated. Published novels, memoirs, poetry collections, non-fiction books, articles, short stories and blogs are tangible results of the group’s success.

Throughout the GWG’s development Susan Tiberghien has remained firmly at the helm. Thanks to her remarkable capacity to network she has brought fine instructors to Geneva. She has generously and intelligently encouraged countless writers to get their words out, to believe in their potential. I have been a member of the GWG since its embryonic gestation and I have seen how Susan’s love of the beautiful art of writing helps diminish that which is ugly, shabby, or vulgar. Though writers should not be guardians of morality, nevertheless they search for their truth in full-blown solitude. The Geneva Writers’ Group not only offers them professional instruction and assistance but it also offers them a home to befriend others who share their passion for words. As Susan says, “the continuing expansion and creative spirit of the GWG is due to its family of members, the old-timers who welcome the new ones, and to its steering committee that expands to twelve every other year for the Conference.”

GWG website: www.genevawritersgroup.org

March 2, 2011 - Obituary for a Christchurch Home

This morning I received an email from the city of Christchurch in the South Island of New Zealand:

“Our home moved on its foundations and the roof is ready to cave in. The stone fireplace fell and the chimney collapsed. The plaster on the walls has peeled like a banana. The conservatory dropped, windows broke. Cracks are everywhere, especially in the foundations. The house moves, creaks and shakes with aftershocks, which are coming within minutes of each other. We have received the red sticker for demolition.”

I was asleep in Switzerland when the earthquake struck Christchurch. Twelve hours separated me from New Zealand – they were already into the next day’s afternoon. My floor trembled and I swayed against the door.

My childhood home was built by my parents on a hill that looked out over Christchurch towards the Southern Alps. We moved in when I was four years old in 1949. Calmed by the protective shelter of giant eucalyptus, which towered over our glass and stone house, I found a haven.

Months before, a fire had roared through our apartment building one night. When the fire was put out only the stench of wet cinders and a faint glow of broken beams remained in the dawn light. I could not get dressed – my shorts and sandals were devoured by flames. The little chairs and table where my brother David and I drew pictures evaporated, and even White Bear, who had never left me before, had disappeared.

But on Aynsley Terrace, a house rose up that would not burn down, a house designed by my mother, that had a room only for me, with twin beds covered in blue eiderdowns and a desk built into the wall. My father and I planted hollyhocks underneath my window and a china doll joined me for company. Terraces lead down to the river Heathcote, one terrace had an old walnut tree where a swing was placed. Ice plants and wild geraniums covered rock walls, built by my father with help from other family members. From the bay windows the green copper dome of the Basilica and the Christchurch cathedral spire reassured me. God was centered in our city.

When I saw on television that the cathedral was destroyed as if a bomb had fallen on it, suddenly I heard David singing and felt my grandparents’ presence next to me as we listened to him. For a time, David had been the choir’s soloist. His voice seemed to reach every corner of the high vaulted roof. I learnt that tourists had been on the cathedral tower when it swayed and fell.

Twenty-four hours passed until my loved ones were accounted for. I was aching for people I no longer knew – the girls I’d gone to school with who were now grandmothers, neighbors who had watched the city grow and had grown with it. My life in Switzerland continued, but part of my mind was roaming around the Christchurch streets as the dead were buried, possessions retrieved, lost pets hunted and cars dug from the mud.

When I was eleven years old I left Christchurch for the United States, never to return to the city, except for a three-day visit when I was thirty. My parents had taken us away as parents do, but I never wanted to leave. I thought it inconceivable that we would ever abandon the shelter of our home. But when a family arrived to visit the house and two little girls bounced on my blue eiderdowns and fought over who should have which bed, I knew again that empty ache of loss.

Over the years I grew used to the feeling. Good things happened to me and I moved on. But in my mind I kept a magic place and sometimes returned to it. I became a ten year old again, playing in the conservatory, living make-believe adventures.

This morning the email arrived. It came from one of the girls whose parents had bought our home. She moved in after her parents moved out and her own children had grown up there. She knew her home was beloved ever since it was conceived in my parents’ minds. I cried … no, I howled … not ashamed to admit that the house was like a member of the family. I am only grateful it did not take a human life when it died.

August 18, 2010 - International PEN

The logo of International PEN

The international logo for PEN (see above) unites three initials: P for poets & play writers, E for essayists & editors and N for novelists and non-fiction authors. International PEN is a world association of writers, founded just after the Great War in 1921, in London, by Mrs. C. A. Dawson Scott, a writer and active feminist. She wished to bring together authors of different nations to uphold the liberty of expression and favor good will and respect between people. Her idea succeeded probably beyond what she had ever imagined; in 2010 there are 145 centers through out the world with more than 15,000 members.

With time, several committees developed within PEN, focusing on particular problems that confronted writers. Writers for Peace and Writers in Prison are two important areas that concern many writers, as well as translation and linguistic rights, writers in exile, an emergency fund to help imprisoned writers’ families, and women writers’ specific topics. I will offer only one statistic that explains much of PEN’s work: according to the International Federation of Journalists, 137 journalists and media workers were killed in thirty-six countries in 2009.

So why am I a member? First of all, I am grateful for the liberty to say and write what I think. By participating in PEN I am publicly committed to help writers who do not have these fundamental rights. Second, I believe in the power of words – many times I have seen one person’s words change a situation. Why else are leaders or governments so concerned when it comes to keeping journalists in control, surveying websites and emails, engaging communication experts for their own interests?

My third reason is the difficulty in learning how to connect with others while keeping an open mind and a respectful attitude. Good writers speak their minds and no mind is the same as another. Ever since PEN was founded the intrusion of politics has been a source of debate. The centers try to respect one another’s autonomy of judgment, just as members of each center do the same with each other. Unfortunately, like religion, politics often mean passion and PEN is a perfect place for intellectuals to learn to listen and receive the other’s argument without offense.

In PEN Centre Swiss Romand, founded in 1944, I have learned a great deal about tolerance. Many foreigners are established in the French-speaking part of Switzerland, especially around the Lake Geneva area and many, who are writers and/or journalists, belong to PEN. Therefore the PEN Centre Swiss Romand is an active beehive because these members have often been out front where oppression and violence occur. In meetings, these strong-minded people can clash like Titans and it is not always easy to follow their line of thought.

But their work is magnificent. Five members are engaged actively in Writers In Prison and/or Writers For Peace. Fawzia Assaad is International PEN’s delegate at the United Nations’ Human Rights Conseil, Hoang Nguyen Bao Viet follows writers’ problems in Vietnam and Mynmar, and Dinah Lee Küng does the same for China. Mavis Guignard faithfully produces a quarterly news bulletin on the Writers In Prison committee’s work and other news. One member, Susan Tiberghien, founded the Geneva Writers’ Group with active members from over thirty countries and there are others, each committed to International PEN’s ideals.

I am proud to be a member of PEN Centre Swiss Romand and I salute my fellow members in this simple blog for all the time and energy they offer so that other writers may enjoy one of our fundamental rights – freedom of expression.

July 11, 2010 - Château de Lavigny

Most writers have a life beyond their computer and I have always been curious how fellow writers balance their work with other responsibilities. A novel, play, or poem doesn’t just happen. Months of mental meandering may occur before the first word appears. But this activity comes without a salary. Of course, many writers have university grants, government allowances, generous family members, inheritance, and other sorts of financial and practical help to assist them. But what about those writers who are without such help?

Most writers have a life beyond their computer and I have always been curious how fellow writers balance their work with other responsibilities. A novel, play, or poem doesn’t just happen. Months of mental meandering may occur before the first word appears. But this activity comes without a salary. Of course, many writers have university grants, government allowances, generous family members, inheritance, and other sorts of financial and practical help to assist them. But what about those writers who are without such help?

When I began my writing career I used to dream of a regular income and a cottage by the sea, Ireland seemed ideal, where I could be alone with my imagination. Does this sound familiar?

Fortunately, many countries have developed writers’ colonies where artists may retreat for a while and concentrate on their art. Between Lausanne and Geneva, in a village overlooking the lake and the Alps, a quiet, elegant retreat exists where writers from all over the world may go for three weeks and be left alone to write. The submission directives are simple – the applicants should have one book published (not self-published), speak fluent English or French and be able to pay their travel expenses.

Two decades ago, Jane Ledig-Rowohlt bequeathed her fortune and her home, the Château de Lavigny, to be used as a literary colony in memory of her husband Heinrich Maria Ledig-Rowohlt. A “spirit of international community and creativity” was the foundation stone for the establishment. For the last fifteen summers, in five different sessions, up to eight writers are provided each with a private room, all their meals, and time to write and to discuss their ideas with their companions. Once a session, on a Sunday evening, local guests are invited to a reading performed by the residents.

Whenever I go to the readings I am struck by the music of the different languages. The writers often recite part of their work in their mother tongue, be it Mandarin or Swahili. There are unusual rhythms and rhymes and something faintly exotic as if I have traveled across oceans and continents. I recognize the contentment of children who play together though they do not understand one another’s language.

The legacy of Heinrich Maria Ledig-Rowohlt continues to penetrate the Château de Lavigny. He was a great editor and translator, a man who influenced international publishing and contributed to the cultural rebirth of post-war Germany. In the 1930s he was already bringing internationally celebrated authors to German readers and after the Second World War he continued to remain open to new trends while still keeping his publishing house’s high-quality literary tradition. His list includes the works of such writers as Ernest Hemingway, William Faulkner, John Updike, Gunther Grass, Albert Camus, Jean-Paul Sartre, Italo Suevo, Henry Miller, James Thurber, Harold Pinter and Vladimir Nabokov. But most of all, Heinrich Maria Ledig-Rowohlt cultivated friendship and generosity with his protegés. The Château de Lavigny contains letters from many grateful authors speaking of these qualities.

editor and translator, a man who influenced international publishing and contributed to the cultural rebirth of post-war Germany. In the 1930s he was already bringing internationally celebrated authors to German readers and after the Second World War he continued to remain open to new trends while still keeping his publishing house’s high-quality literary tradition. His list includes the works of such writers as Ernest Hemingway, William Faulkner, John Updike, Gunther Grass, Albert Camus, Jean-Paul Sartre, Italo Suevo, Henry Miller, James Thurber, Harold Pinter and Vladimir Nabokov. But most of all, Heinrich Maria Ledig-Rowohlt cultivated friendship and generosity with his protegés. The Château de Lavigny contains letters from many grateful authors speaking of these qualities.

In reality, these qualities are still within the castle’s grounds. You hear the result in the readings. I have copied out a poem written by a Ukrainian poet, Natalka Bilotserkivets, who read to us last Sunday evening so that you may share in the pleasure.

Angels’ Wine

There’s a peaceful place of girls, flawless as crystal,

of unbreakable children, strong as steel,

where snake-victors in silent, frozen halls

sip angels’ wine dropped to their knees.

There’s a peaceful place of surrendering grasses

where the dragon sings for all undying hours.

He bids his time, wise head bowed,

a brocade of wings embroidered with flowers.

Monks dwell in cells of burgundy-colored rocks.

Poverty burns inside their bowls.

Angels’ wine has neither been seen nor tasted

like tears lost to a river or in our elapsing souls.

The scorpion sleeps at the foot of the rhododendron.

No victories or failures prevail.

And in the window’s light, a sacred darkness.

Like script on a scorpion’s scales.

(by Natalka Bilotserkivets)

May 3, 2010 - BooksBooksBooks

BooksBooksBooks

Lausanne’s Independent English Bookshop

One of Lausanne’s fascinations is its long literary history in the English language. Many visiting writers gained  inspiration and renewed energy while staying there. Edward Gibbon completed The Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire in Lausanne and after Lord Byron visited Gibbon’s home with his friend Percy Shelley, he checked into a lakefront hotel, still in existence, and wrote his famous poem The Prisoner of Chillon. Charles Dickens stayed in Lausanne in 1846 and the countryside helped him to continue writing when he felt submerged by financial difficulties. Perhaps the loveliest description of the lake view, so often admired from Lausanne’s hills, was made by Walter Scott who wrote: “This lake seems so tenderly loved by the mountains.”

inspiration and renewed energy while staying there. Edward Gibbon completed The Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire in Lausanne and after Lord Byron visited Gibbon’s home with his friend Percy Shelley, he checked into a lakefront hotel, still in existence, and wrote his famous poem The Prisoner of Chillon. Charles Dickens stayed in Lausanne in 1846 and the countryside helped him to continue writing when he felt submerged by financial difficulties. Perhaps the loveliest description of the lake view, so often admired from Lausanne’s hills, was made by Walter Scott who wrote: “This lake seems so tenderly loved by the mountains.”

Unfortunately, Lausanne has not really exploited this legacy. Two years ago, when Matthew Wake, a young Englishman, was reflecting on a career change he felt Lausanne could support an English bookshop. He believed if the shop was in the middle of the community it could be a place to browse and buy good books as well as the nucleus of a creative and literary animation for the large number of resident foreigners as well as the local Swiss.

Matthew is a man who follows his heart. After completing a degree in East Asian Studies at the University of Sheffield, he spent two years in a village on Amakusa, one of Japan’s smaller islands, where he taught English, gained fluency in Japanese and became interested in the martial art Kendo, where he holds a fourth degree black belt. After a short stint in London he moved to Switzerland to marry Sylvia, a Swiss Canadian. They have two children. After six years in marketing, with his family’s approval and a viable business plan, Matthew opened BooksBooksBooks on the top floor of Globus, a department store in the old centre of Lausanne.

“I have always done my thing,” Matthew told me when I questioned him about the sheer audacity of his independent venture in a time of universal business consolidation and growing doubts about the survival of printed books. Matthew agreed the bookshop meant more responsibility and stress than he had first imagined, but then he added that any adventure demanded a personal effort.

“I have always done my thing,” Matthew told me when I questioned him about the sheer audacity of his independent venture in a time of universal business consolidation and growing doubts about the survival of printed books. Matthew agreed the bookshop meant more responsibility and stress than he had first imagined, but then he added that any adventure demanded a personal effort.

BooksBooksBooks is now the centre of many literary offshoots. There are three book clubs, a children’s reading club, a women’s entrepreneur group and a writing group, Lakelines Circle, which meets in the shop once a month. Reading events are held regularly with authors from all over the world. Customers are encouraged to bring friends and new ideas.

“Amazon is an anonymous way to buy books. Here you can spend time perusing books and I can order any book you want if it’s not on my shelves,” Matthew said. I agreed. After being frustrated and lonely without a local bookshop, I was delighted to see familiar faces on the shelves again and run through all the new titles on display. There was no way an online bookshop could compete with such physical joy. “Support us and I’ll support you,” Matthew told me and, as a writer and a reader, I knew I’d come home to where I belonged.

BooksBooksBooks

the English bookshop

rue de Mercerie 12,

1003 Lausanne

tel: 021 311 25 84

April 16, 2010 - Is There A Book In You?

A few days ago I was invited with two other writers, Susan Tiberghien and Daniela Norris, to give a talk to the Geneva Women in Trade (GWIT) about writing and publishing. We each first gave an introduction and shared our own personal relationship to the title of the conference – Is there a book in you? Here is my text.

***********

Is There A Book In You?

“I had a farm in Africa at the foot of the Ngong Hills….” Karen Blixen’s first sentence in her novel Out Of Africa sounds like the beginning of a tale she might have told her friends, Denys Finch Hatton and Berkeley Cole, after an evening meal together. It echoes like “Once upon a time…”

Ever since the human race has existed we have narrated or sang stories. While listening, we feel the fluid movement of time. Over centuries, stories were embellished, but usually the storyteller remained faceless. But several hundred years ago, during the fifteenth century, this all changed when a mechanical devise called the printing press was invented. Mass-produced books, self-contained and unalterable, were neatly lined up on shelves. Writers developed names and reputations. This Printing Revolution changed our minds; we were no longer listeners but readers.

Some five hundred and sixty years later we find ourselves at the beginning of another revolution – the Electronic Revolution. Once again our mindset is changing. Our attention span is shortening because we constantly deal with several things at once, switch channels or press keys for continual change. We do not know yet what will happen to printed books. Like jet lag, which is only fifty years old, we are dealing with new phenomena.

And yet we still have stories to tell. Each of us has a story. Yes, I believe we all have a book inside us. But why do we have to tell stories? Doris Lessing has a good answer to that question. She thinks we have a pattern in our minds that obliges us to conform to, so we shape a tale which needs a beginning, a middle and an ending, just as our lives have a pattern – we are born, we grow older and then we die. We need to know what will happen next.I also believe we need to name things. We need to be specific. Language does not belong to the abstract world but is close to the ground. Its base is broad and low and it is our connection to the earth. Or as someone said; God is in the details and we need this relationship.

So why did I choose to be a writer? I am convinced there were two decisive moments in my early life. The initial one was during my first year in school when I was five years old. My family had read Beatrix Potter’s books to me until I knew many by heart, but I could not understand the symbolism of letters. Although all my classmates were deciphering the alphabet I remained an angry, frustrated little girl, quite incapable of reading. One day I was given a page with a drawing of a bed frame – there was the headboard, the mattress and the footboard shown from the side. Next to it were three letters – bed – and suddenly I saw in those letters a bed. This was a moment of great excitement. I had discovered a new and fabulous game. Reading. Words became a love story or as I can still say – this love was an endless story.

The second event happened a year or two later when I was sent to boarding school. The first day was one of anguish. During the recreation another girl, dressed just like me in a green tunic and striped tie, asked my name. I should have replied Jo Ann, but suddenly I was seized with a need greater than I have ever known and I blurted out, “Josephine Jane Elizabeth Anne.” What delight – my imagination had galloped to my rescue and I was no longer a lonely little uniformed schoolgirl, but a princess with a magical name. I had attuned myself to the hum of my universe. I followed up with much embellishment and my new friend and I spent many hours living in this kingdom. This then was my second love –storytelling, which I turned into the solitary task of writing stories.

Much later I came to understand that the supreme irony of writing is that though it starts out for yourself it is ultimately received by someone else.

The only other remark I would like to mention is one made by the American writer Ursula K. le Guin. She wrote that in the year 2000, “for the first time ever, we have kept the perceptions, ideas and judgments of women alive in consciousness as an active creative force of society for more that a generation.” This seems to me to be at least one good reason to keep on writing, reading and telling stories to one another.

March 26, 2010 - Three Writers, Three Precursors

“There’s a river of birds in migration, a nation of women with wings.”

“There’s a river of birds in migration, a nation of women with wings.”

Jan Phillips – author & speaker (www.janphillips.com)

******

Throughout the centuries, foreign writers have lingered by the Swiss shores of Lake Geneva, often motivated by the region’s natural beauty and the tolerant politics of local inhabitants. As a writer and resident of the area I would like to share my admiration for three women, Germaine de Stael, Mary Shelley and Hilda Doolittle, who produced literary works of value while staying here.

Unfortunately, Madame Germaine de Stael, (1766-1817), of Swiss French origins and one of Europe’s modern literary and political dissidents, found little comfort in her charming family home in Coppet village near Geneva. Madame de Stael, a brilliant child of the Enlightment, who believed in reason and progress, felt only bitterness, frustration and grief at being exiled from Paris by Napoleon for her verbal and written critics about his policies, sent far away from the pivotal events, which were taking place there and throughout Europe.

In 1813, De L’Allemagne was published in England, after another skirmish with Napoleon when the emperor tried to destroy all known copies because he believed the book to be personally insulting. In reality, with this book, Madame de Stael bridged the gap between Neoclassicism and Romanticism, while explaining Germany and its people to the French. She was one of the first to espouse the European ideal.

Another book, Dix Années d’Exile, written over a period of five years and unfinished at her death in her home in Coppet, remains a riveting memoir. It tells about her first meeting with Napoleon and of her admiration for the great republican liberator and military genius, and then her growing concern for his drive to absolute power, quite contrary to her belief in more moderate political systems. There are details about the constant harassment she endured by his military police as well as anecdotes of her travels through Russia during the French invasion. Seen now, through the telescopic time lens of two hundred years, the discord between Madame de Stael and Napoleon was a classic conflict between the pen and the sword. Nevertheless, perhaps the most penetrating insight about Madame de Stael was made by Napoleon himself, before they became enemies, who remarked; “She teaches people how to think who have never thought before, or who have forgotten how to think.”

******

Like Germaine de Stael, The English writer Mary Shelley (1797-1851) was the daughter of two liberal parents and she also received a decent education and met many of the intellectuals of her time who came to her father’s home. If Mary was recognized as the poet Shelley’s muse, she was always a person with a mind of her own.

In 1816, when Percy Shelley and Mary, then nineteen years old, decided to take a summer residence near Geneva, they had already spent two years together and had a son William born earlier in the year. Their small house near the lake lay just below Byron’s stately residence, the villa Diodati. The weather was cold and wet and most of their evenings were spent talking as they sat around a warm fire. Percy Shelley was fascinated, not only with the new rational developments in science, but also with the gothic supernatural. Quite naturally, one evening, Lord Byron suggested they each write a ghost story. Out of Mary’s imagination, from her youthful, intuitive dream-like vision and the raw material of spirited scientific conversations, Frankenstein was born. This famous work of science fiction was the fusion of two lines of thought and is considered the first important example of horror fiction, which is still popular in present-day literature.

Frankenstein or The Modern Prometheus is a surrealistic story with a central theme of revolt against divine oppression. Today we can read it as a clash between fixed religious beliefs and science, between doubt and certitude, but as Mary later pointed out very clearly, it was not The Monster, but the scientist, named Frankenstein, who discovered how to create life, who was the amoral product of nature without passion or responsibility. Mary’s novel is clearly a warning to all who believe that modern industrial and post-industrial research and development will establish peace and prosperity on earth.

******

My last writer, the American poet Hilda Doolittle or H.D. as she was usually called, (1886-1961) settled by Lake Geneva in the 1920’s with her wealthy mentor and lover Bryher, née Annie Winifred Ellerman. Around this unusual couple were a group of unconventional and talented people, among them Ezra Pound and Richard Aldington who along with H.D. had formed the original nucleus to the loosely affiliated British and American poets called Imagists. Shortly before W.W.1 they had challenged the Romantics through a radical new form of poetry, – tight, concise free verse, – which laid the foundations of modern poetry.

When H.D. moved from Britain to Switzerland she was already breaking away from the Imagist label, seeking new ways to deal with her creativity, inhibited by predominately male traditions and critics. Conflicted by her heterosexual and lesbian desires, she turned to Greek classics and myths, in hope of developing a cultural transformation.

By Lake Geneva the couple entered a ménage-à-trois with the painter Kenneth Macpherson who was passionately interested in films. This trio of enthusiastic inter-war intellectuals formed the famous Pool group to encourage new forms of films and literature. Their most famous production was the silent film Borderline, written and produced in Switzerland in 1930, along with its film journal Close Up. Borderline is a classic of early experimental cinema, daring in subject with its interracial love triangle. Paul Robeson, an African American and one of the most famous international cultural figures of the first half of the 20th century, stars in it alongside his wife and H.D.

The Pool trio built a magnificent Bauhaus-style home that doubled as a film studio in La-Tour-de-Peilz, overlooking Lake Geneva. When I visited it a few years ago it seemed that the forgotten energy and excitement of these exceptionally talented people still existed within the ship-like white walls.

H.D. was always in search of a certain unity within her own life and in the world around her. Due to the complexities of her relationships and her fragile emotional state, H.D. decided, with Bryher’s financial assistance, to undergo psychoanalysis with Freud. This led to a certain mystical feminism and her last poems show a re-vision of patriarchy. In her poem Helen in Egypt she deconstructs Euripides’ play and re-interprets the Trojan War, and by extension, war itself. After her death, when rediscovered in the 1970’s, she became an important icon for the modern feminist movement and for gay rights. The Goddess in her later poems was no longer a mythical symbol, but the expression of the Divine Spirit.

When I think of the lives of these three writers, I remember their efforts to bridge the conflict between their often traumatic private roles as wives, lovers and mothers and their professional role as writers. In the early morning, when I gaze from my kitchen window at the sunlight glittering on the surface of the lake, I remember these women and see them as precursors, light bearers, for those who write by Lake Geneva’s shores today.

******

She carries a book but it is not

the tome of the ancient wisdom,

the pages, I imagine, are the blank pages

of the unwritten volume of the new;

all you say, is implicit,

all that and much more;

but she is not shut up in a cave

like a Sibyl; she is not

imprisoned in leaden bars

in a coloured window;

she is Psyche, the butterfly,

out of the cocoon.

( Taken from H.D. ‘s poem Tribute to the Angels)

.jpg?v=1g2sobq)